I've been a Mozart fanatic for as long as I can remember, and his music is absolutely central to my life -- outside my career as a violinist, that is. I've conducted his operas, symphonies, and concertos; I've written a book on interpreting his instrumental works; I jump at any opportunity to coach his chamber music; I routinely try to pick my way through the solo parts of his piano concertos at home when nobody's listening...and yet for some reason I've rarely found occasion to actually perform his string music, preferring instead to engage with it as a conductor, teacher, or author. Maybe I've been just a wee bit scared of the enormous challenges, both interpretive and technical, he throws at us violinists!

But this summer, my relationship with Mozart changed. I finally gathered the courage to embark on a recording project exploring his string writing. I experimented quite a bit along the way, and I learned a lot in the process!

Where does one begin when trying to get inside Mozart's violin music? Pianists have it easier than we do, since the piano concerto served as an artistic vehicle for the entirety of Mozart's life and career, meaning that any point of entry into the repertoire is sure to yield interpretive riches. Mozart first dipped his toes into the genre of the piano concerto at age 11, with four pastiche concertos arranged from music by contemporary composers, and he wrote his last piano concerto in 1791, his own final year. This means that his piano concertos chronicle a good 25 years of his stylistic explorations. By contrast, his violin concertos are youthful pieces, all dating from his teens. They provide a snapshot of his development at a single moment, but they are not mature masterworks. And even broadening the purview to include pieces outside his official five concertos, such as the "Haffner" Serenade K.250, or the spectacular Sinfonia Concertante K.364, we remain in the early phases of Mozart's musical development. The "Haffner" dates from 1776, only a year after the A-major violin concerto, and the Sinfonia Concertante from 1779, when the composer was just 23. The music is great by any measure; yet it clusters at a single moment of his life, and it can feel limited.

Why does Mozart turn away from the violin concerto at this point in his life? It's not that he abandoned string writing altogether -- though he did announce to his father, in a letter of 7 February 1778, that he planned to stop performing publicly on the violin in order to focus his efforts on the piano and composition. And with this turn away from public performing as a violinist, his innovations with the instrument shifted away from music for the concert stage, relocating instead to the home and salon, where Mozart continued to play the violin and viola as a chamber musician. It comes as no surprise, then, that beginning in the early 1780s, the string writing in his chamber music became more daring and more complex. Thus, I elected to begin my explorations in that world -- not with the quartets or quintets, but with the two extraordinary duos for violin and viola, K.423 and K.424. I spent spring and summer of this year preparing these remarkable pieces with the intrepid Catherine Cosbey of the Cavani Quartet and McGill's violin faculty, and we took them into the recording studio in June. The other works on recording are the Violin Sonata in A major K.305 in an anonymous arrangement for two violins published around 1799, as well as selections from Mozart's final opera La Clemenza di Tito in an arrangement published around 1800. Although Catherine is primarily a modern violinist, we used a period-instrument setup. I played viola for half the recording and violin for the other half. Despite my longtime professional association with Mozart, the experience was by turns challenging and revelatory.

Perhaps the primary discovery I made during this process -- maybe it sounds obvious in hindsight, but I didn't take it for granted at the start! -- was just how good Mozart's violin-viola duos are. Of course I had played them recreationally before, but I had never actually learned them properly or interpreted them, and I was unprepared for their astonishingly high quality. Many academic discussions of the duos focus on the fact that Mozart wrote them as a favor to Michael Haydn, who was unable to finish a set of six duos and requested that Mozart provide the remaining two. In such discussions there's often an implication that Mozart tailored his duos to match the quality of Michael Haydn's less inventive efforts. But nothing could be further from the truth. I discovered, approaching the pieces this year, that there isn't a lazy phrase to be found. This is true, first of all, on the level of sheer compositional technique. Mozart's craftsmanship is always astonishing. Consider, for instance, the first movement of the G-major duo K.423, whose second theme is full of subtle wit. The melody seems unassuming enough, but look closely and you see that each zigzagging interval is one step larger than the previous one. The theme begins (m. 27) with an ascending second, followed by a descending third, ascending fourth, descending fifth, ascending sixth, and descending seventh - a fun effect in itself, since Mozart somehow manages to bring this off without warping that old standby of a chord progression, I-V-vi-IV, or undermining the tune's lyricism. After this wedge-shaped bit of melody, in m. 29 the sixths and sevenths catch on and spin out into a melodic answer in their own right, even as they continue to push lower and lower, the harmonic rhythm increasing before steering to a cadence.

So far so good. But in the recap, when the theme returns, the descending answer runs away with itself. The viola begins the gesture in m. 118. But instead of successfully bringing about a cadence, as the violin did previously, the two players get tangled up, endlessly tossing the melody back and forth and continuing to desperately transpose up so as not to crash into the bottom of their instruments' ranges. They keep this process going for so long that, if we removed the ascending leaps, the whole passage would plunge down more than four octaves. Meanwhile, as the players get lost in the tangle, chromaticism creeps in, and by the time the violist starts in on the sixteenth notes in m.121, things seem to be spiraling out of control! Yet somehow we arrive back on the necessary predominant in m.122 and come, once again, to the polite cadence a bar later.

Beyond such compositional cleverness, the duos are impressive for their expressive range. We find in them a massive store of operatic references -- there are phrases and melodies in the last movement of the G-major duo that come to feature in Don Giovanni, and throughout the B-flat duo that come to feature in Die Zauberflöte. Most of all, however, I'm struck by Mozart's textural ingenuity. Even with only two instruments at his disposal, he simulates a dizzying number of non-duo textures, from the string quartet (when both musicians play double-stops, yielding four-part writing) to horn calls, symphonic fanfares, an aria, and more. Taking this in, and considering that Mozart composed the duos in late 1783, I found myself understanding that this is where he really learned how to write for strings. By the time he wrote the two duos, he had completed only one of the mature, "celebrated" string quartets, and in the duos' immediate aftermath he would write five more in relatively rapid succession. Perhaps the burgeoning textural and instrumental ingenuity in those quartets was sparked by the creative constraints he faced here, in writing for only two instruments.One of my Mozartian obsessions is musical character. It's often said that Mozart's output is fundamentally operatic, and I wholeheartedly agree. Every phrase suggests a character of some sort, and the duos are no exception, whether in the literal operatic references (for instance, Donna Elvira's aria "Mi tradì" makes a brief appearance in the last movement of the G-major duo, m. 96-97) or through more general references -- here a gesture implying the gravitas and menace of The Count, there an amorous march redolent of The Countess, elsewhere the patter of Figaro or Masetto. The question I sometimes wonder about, however, is not whether there are "characters" present in the music, but how to tell where one character ends and another begins. Do we divvy up expression at the level of the entire phrase? Of the half-phrase? Perhaps by the bar, or even the beat? I feel that this may be the most pressing challenge I face when interpreting Mozart.

In some rare cases, Mozart makes it very easy to tell where one character ends and the next begins. Consider, as an example from a different work, the familiar first movement of the G-major violin concerto, mm. 64-68. The contrast between the staccato marks and slurs, which suggests a broader expressive contrast between implied fanfares and swooping, lyrical gestures, makes it clear that the passage implies a dialogue, and that the characters shift back-and-forth by the bar. No problem there! But the situation is usually more ambiguous. How many expressive stances might we find, for instance, in this unassuming passage from the slow movement of the G-major duo K.423?

On first glance, it might seem like just one: some sort of a "singing" melody in the violin, tied together with the two rhyming downbeats of m.9 and 10, all above an unobtrusive accompaniment in the viola. But, looking more closely, each bar also carries its own expressive implications, and the whole progression tracks a series of highly distinct gestures, perhaps even a hint of dramatic narrative. The first bar shown here, m. 8, features a slinky, intense chromatic line. Indeed, when we hit G# on the downbeat of m.9, there's even a small moment of uncertainty: is it an A flat, and have we just veered into F minor? (The movement is marked Adagio, so between the slow tempo and a touch of rubato to elongate the G sharp slightly, the suspense is not negligible!) But then the note resolves up to A, and we remain safely harbored in F major. ("Phew! That was a close call!") The ascending figure later in m.9, with its delightful dotted rhythms, seems to laugh after this brief musical double entendre. ("Did someone say F minor? Not me! Hah!") The bar might be played in a way that is dainty, almost coy. And then the trill-and-scale in m.10 seems altogether more lyrical, confident, and operatic. Viewed thus, the character changes by the bar -- and this rapid succession of implied expressive states is a challenge to bring out. Both performers need to remain constantly alert for opportunities to deploy those small shifts of inflection so as to convey the whole story.In other cases, meanwhile, the question of how quickly expressive states shift is moot: it might be clear that one character persists over a long stretch of music. Even in those cases, however, identifying a phrase's expressive world is not always a simple matter. For me, playing viola in K.424, I faced this challenge most directly in the slow movement. The violinist doesn't need to entertain any doubt: Mozart marks the movement "cantabile" and spins out one of his most operatic melodies:

For the violist, however, the nature of the phrase is far less obvious! What kind of accompaniment is this? Preparing for our recording, we experimented with a range of options. The usual approach, and the first we tried, is to play the accompaniment fully legato, in the style of a wind serenade -- as if scored for basset horns and bassoons. We also experimented with bowings, trying both linked and unlinked versions of the quarter-eighth rhythm. Then we explored a totally different conception of the piece, playing the viola part very staccato (except when there are slurs), and imagining the accompaniment as if scored for a strummed instrument like guitar or lute. I even tried it pizzicato once or twice! We tried, too, a middle-of-the-road version -- what I thought of as staccato with a dab of "fake reverb". For the recording, we ultimately settled on doing it mostly staccato: not actually plucked, but light and short enough that it would sound song-like. But, even though that's how we recorded it, it's clear that the choice might be wrong. The piece remains elusive, and I have no doubt that when I next perform it, I'll feel differently about the articulation and, by extension, the expressive nature of the movement.One final realm of experimentation in this recording was embellishment. This, too, has been central to my Mozartian explorations in the past -- I write about it in Chapter 4 of my book, as well as in this open-access article. Although we know that Mozart himself was a habitual ornamenter, and he expected his contemporaries to creatively intervene in his works by adding extensive embellishments, many string players have been slow to take up the challenge. Period-instrument pianists are generally more willing -- Robert Levin's complete cycle of Mozart's piano sonatas is a fascinating example of the interpretive riches that flow when a performer is sufficiently uninhibited! -- and in approaching the duos we set ourselves the task of bringing the same ethos into Mozart's string music. Of course, the situation in a duo is a little different from that in a sonata: an individual pianist can intervene in a musical text without worrying about how any embellishments might affect other performers' lines, whereas in a duo the players need to respond to each other. Even so, in this recording we went all-out.

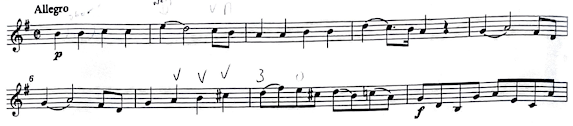

We started by adding significant embellishments in all repeated passages, which was Mozart's own practice. This means that embellishments -- sometimes so dense that they seem more like wholesale variations -- feature in the repeated exposition from the first movement of K.423 as well as in smaller-scale formal repeats, such as reprises of the rondo theme in the last movement of K.423 and all the repeats in the variation movement of K.424. Throughout, we attempted to mirror the style of embellishments Mozart uses in the handful of movements for which he provided models. Here's what we came up with, for instance for the rondo-finale of K.423. Mozart's original theme runs:

Our embellishments for one of the melodic reprises (the handwritten passage pasted into the score):

We wrote different embellishments for each appearance of the theme, increasing the density of additional notes every time the theme recurs. In another case, in the slow movement of K.423, we drew embellishments from the first edition of the piece, published shortly after Mozart's death. The Bärenreiter edition excludes these because they can't be confirmed to have originated from Mozart; but we thought the style was convincing, so we re-introduced them! And even if they weren't written by Mozart himself, they are contemporaneous, so they certainly reflect historically-appropriate practices:

Finally, we added cadenzas at every fermata, and even placed one or two brief extra cadenzas in the outer movements of K.424 where no fermata is indicated but where we thought Mozart might have expected a touch of improvisation. We generally tried to base these, too, on models: for instance, the cadenza we added in the K.424 variation movement imitates the cadenza Mozart wrote for a piano variation set. For the other cadenzas, we drew from motifs in each movement and did our best to match Mozart's style.

It's been an exhilarating and rewarding experience to get inside this music and to try to give it fresh, creative life. The final product is due for release in November. I certainly hope this will be but the first step in a longer-term project featuring similar expressive experimentation with Mozart's other, later string chamber music -- but in the meantime, we have another round of edits to check!