This weekend, I attended a marathon performance of all of Beethoven's violin sonatas in a single concert, organized by one of my McGill colleagues as a studio project. Each of her students (plus two participants from other violin studios) paired up with a pianist to learn and polish one of Beethoven's ten magnificent violin sonatas. Along the way, a wide range of other colleagues attended studio classes to coach the students (including a modern piano professor, our historical keyboard professor, and me, as a historical violin and musicology professor), and then, this weekend, the whole gang got together to present the cycle in public, moving chronologically from Op. 12 no. 1 all the way through Op. 96. (Studio teachers, take note! This was a fabulous experience for everyone involved.)

I love the Beethoven sonatas dearly, and I know them well, having performed the cycle a few times on period instruments. But as a performer, I've always split the sonatas into three concerts, which in turn could be separated by days or even months. I had never heard the whole cycle live in a single event--and this listening experience alone was edifying and instructive. There is the sheer creative ingenuity Beethoven exhibits across the set. It feels like each work is a fresh attempt to solve the problem of how to write for these two instruments. Not once did my attention flag. I also marveled at Beethoven's creative development across the set. Unlike his piano sonatas, symphonies, and quartets, which are spaced more evenly across his career, the violin sonatas are chronologically lumpy. He composed the first nine within about five years (c.1798-1803) but waited nearly a decade before writing the final sonata, in 1812. This, too, is remarkable. I still find it hard to believe that the first sonata and the "Kreutzer" have only half a decade between them--that an artist can undergo that much growth in such a short span of time, redefining so many formal and expressive features of the genre. And of course, it was equally uplifting to see ten different students, each a true musical individual at a singular stage of development, grappling with the composer, the music, and the instrument.

Watching this inspiring performance, I found myself reflecting on what it is that makes these sonatas so difficult. Flip through the score: there's nothing in the music that "appears" at first glance to be technically impossible--certainly nothing that even begins to approach the challenges posed by, say, Paganini's Caprices, composed 1802-1817 and thus contemporary to the last five of Beethoven's violin sonatas. And yet, despite the seemingly simple notation, these pieces are incredibly hard.

Many of the challenges Beethoven sets for us violinists in these works are expressive rather than technical. If I had to identify the single most important thing for a violinist to keep in mind while playing this music, it would be this: that we are, for much of the time, accompanying the piano. The late 18th-century violin sonata was a genre in which the piano soloist would take center stage, with the violinist often playing quiet whole notes in support; and although Beethoven does expand the role of the violinist beyond mere accompaniment, very often we are there to bolster the pianist. This is even reflected in the way Beethoven and his contemporaries referred to the genre. Although today we think of these as "sonatas for violin and piano," in the late 18th century they were known as "sonatas for piano and violin."

If you're a violinist starting to dig in to these pieces, one way to begin thinking about your role is to ask your pianist play various passages without you. Sometimes, as in the opening phrases of Sonatas 1, 3, 4, and 8, you'll see that absolutely nothing is missing, that the piece is "complete" even without the violin part. Ask yourself, then: in such cases, what exactly is your job? Why did Beethoven bother writing a violin part? One answer is that the violinist's function is to provide aural "background" so that the pianist can act like a soloist. In Sonata no. 3, for instance, the piano part alone sounds like a coherent solo sonata. Add the violin playing those half notes, though, and you suddenly have an "orchestral" background from which the pianist emerges, like a concerto soloist. (In fact, once you see it this way, isn't the opening just like the beginning of the "Emperor" Concerto?) At other times, as in Sonatas 1 and 8, the unison helps the pianist sound more orchestral. And in Sonata 4, the violinist gets to manufacture the illusion of the piano's resonance, so that the pianist is free to play a clear left hand without obscuring the eighth notes with the pedal. With the violinist's help, the pianist can have it both ways, articulating the left hand while also producing a halo of sound that supports the long slur and adds warmth.

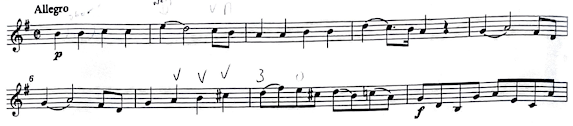

Here's how I usually describe all this: the violinist's job in 80% of this music is to make the pianist sound better. Once you take this outlook on board, so many interpretive matters clarify themselves. Vibrato, tone color, articulation, and the like are suddenly to be used in the service of blending with the piano and creating resonance that is unavailable on that instrument alone. Try, as an exercise, having your pianist play just the left hand along with the violin part, so you can coordinate these matters: you'll find, for instance, that if you really focus on supporting the piano, you'll vibrate a lot less on those long notes than you might have otherwise. One of my favorite passages for this exercise is the theme in the slow movement of the "Spring" Sonata (no. 5). Those interjected quarter-note sighs in the first iteration of the theme, and the syncopated eighth notes and gentle sixteenth-and-eighth-note rhythm when it repeats, need to be both audible and truly in the background, supporting what the soloist does without taking attention away. When the violin plays a dissonance that is absent from the piano part (the G flat in m.35, for example), it's a moment to reclaim aural focus. And even when the task isn't to play an accompaniment "with" the pianist, you can benefit from imitating the pianist's style of executing similar figures. In the slow movement of Sonata 6, don't try to sing out every sixteenth-note triplet in the arpeggiated accompaniment passage in the second half of the movement; instead, ask your pianist to play their version of that accompaniment for you, and try to imitate the lilt so easily achieved when a keyboardist plays that figuration.

Perhaps because the violinist spends so much time accompanying, I've always felt a little strange standing in front of my pianist when I play these pieces. So I generally set up the stage with the pianist in front, while I stand behind and read over their shoulder. The very nicest way to do this is to have the pianist actually facing the audience, the end of the instrument pointed directly out, with violinist standing by the pianist's left side. This is how musicians generally set up in the late 18th century, and it works beautifully in this repertoire. It makes it easier to play in the background, since the piano is, quite literally, in front--and it carries the added benefit of allowing you to actually see the pianist's left hand and adjust your playing in response. The benefits accrue everywhere, but are especially palpable when the violin and piano left hand carry joint accompaniments. Of course, being a historical performer, I'm ok doing wacky things like radically rethinking the stage setup for this music, since I'm not contending with the weight of a modern-instrument performance tradition. But as HIP practices become increasingly mainstream, even modern players might want to experiment with this setup. (And, to their great credit, many of the McGill students did this past weekend!) It really allows both players to make these pieces into the chamber masterpieces they are, rather than putting the accompanist out front while the piano soloist, in the back, does much of the work.

Another set of ideas that can help performers find their way through this music involves understanding the gestures that make up Beethoven's expressive arsenal. I hinted briefly already at the value of thinking this way, when discussing the opening "concerto" passage of Sonata 3. Once you recognize the opening four bars as sharing some elements of the "concerto" genre, your pianist might feel emboldened to play those bars out of tempo, like the quasi-cadenzas they appear to be. This idea can be generalized as follows: always ask whether the texture of a given phrase implies some performance directives. To me, the opening of Sonata 1 looks like the start of a symphony; and this means that my job as a violinist is to help the pianist sound like a full orchestra, complete with strings, winds, trumpets, and drums. This means that I'll limit the vibrato and adopt a different tone color than I would in a more melodic setting. Sonatas 2 and 6 open with what seems more a string quartet texture, with the violinist playing either second violin or second violin + viola, and this in turn carries a different set of associations for phrasing and rhythmic feel.

Nor are Beethoven's signals purely textural. Other rhetorical or expressive gestures come in the form of rhythmic patterns that suggest various dance types, which can also offer insight into tempo and phrasing. The last movement of Sonata 2 is a minuet--so, don't play it too fast, and be sure those lovely syncopations tug against the more usual downbeat-centric hierarchy. Likewise, the second movement of Sonata 8 is a minuet--in this case, don't play it too slowly! And make sure the unslurred quarter-note upbeats to the second melody are light. Other dance-like patterns found throughout these works include gigues (last movement of Sonata 1); contredanse (last movement of Sonata 3); gavotte (last movement of Sonata 8). Other rhetorical markers, meanwhile, are broader and say something about the atmosphere of a piece. Particularly well represented in this cycle are features of the "pastoral" style (drone basses, 6/8 meter, woodwind textures), which show up in Sonatas 4, 5, 8, and 10, and may suggest a less virtuosic, and more muted and intimate style, than what you often hear in modern-instrument recordings.

Of course, despite their often simple appearance on the page, these sonatas are exceptionally difficult. But I hope this brief overview of some of their expressive features helps others find a productive point of entry into Beethoven's writing for these two instruments. Although thinking of the music in such ways does not automatically disarm the technical challenges, I've found time and again that the technical difficulties become less acute with these adjustments of mindset--that accompaniment passages become a little easier to play when we stop trying to emphasize every note, and that even the flashier phrases become more approachable when we recognize them as part of an intimate dialogue with the other performer rather than as soloistic flights that demand high-octane delivery. The dance-like movements, too, become easier when we allow the gestures to have some strong notes and some weaker notes, and when we relax our sound and arms on the lighter parts of the bars. Needless to say, these are just a few of the relevant expressive issues, and there are others as well, for instance the sense of humor that imbues these sonatas, and other kinds of expressive characters. I may revisit them in a future blog--but for now, happy practicing!