Although my previous post here is clearly marked 23 July 2015, I still have a hard time believing that 13 months have passed since I last added to this journal. Now -- with September and a new season in view -- seems a good time to begin again.

To ease in, I'll start by posting a few photos and thoughts from my Telemann recording in mid June. My colleague Paul Cienniwa and I spent two days at WGBH in Boston recording seven early Telemann violin sonatas -- six from his brilliant Frankfurt collection, and one from the Dresden archives that will be a premiere recording. (Who knew there was still unrecorded Telemann out there?)

Although I've participated in other recording projects as part of orchestras and small ensembles, I've never done a solo project like this, so I've never had quite this level of artistic control. Needless to say, I'm still feeling my way through the process. There are so many trade-offs -- for instance, when the perfect takes feel a bit lifeless, but the exciting ones are all ragged. The number of possibilities, too, is numbingly vast. (I left the studio with 300+ takes of a mere 28 movements, and spent about two weeks weeding through them.) I surely knew, intellectually, at least, how artificial the recording process is, but none of my anti-recording philosophising prepared me for the experience of conjuring, take by take, a completely 'fake' interpretation: one in which I know I played every note, but which never, ever, sounded quite that way before, either in reality or in my imagination. And, with so much material, so much of it useable, I could have decided on any number of different final products. For some movements, I constructed four or five take-maps, all viable, and each with its own strengths. At best, it destabilizes the whole notion of the recording as document of an interpretation, and replaces it with that of recording as unconscious inventor of an interpretation.

There's an interesting contrast here with what various philosophers, most ably Taruskin in Text and Act, have said about live performances, recordings, and interpretations. Taruskin looks at a composer-performer like Stravinsky, whose many repeated recordings of his own works are so bewilderingly different, and so often diverge from performance instructions in the score, to argue that there is no such thing as a single 'Interpretation' of a piece of music, even (I say: especially?) by the work's composer. He begins from the 'evidence' of divergent recordings, and extrapolates to include live-performed interpretations on his list of nonexistent things. My experience suggests the opposite trajectory: for me as a performing musician/human, there is never a single interpretation of these works -- but in doing the recording and putting all the 'good' takes together and discarding the 'bad' I've had the rather disconcerting experience of watching an interpretation come to life, seemingly on its own, simply by piggy-backing on the good takes. On 17 June, there was no 'Interpretation'; now there is.

Ironically, and despite having watched the interpretation take shape, I still don't know quite what it will sound like, since I haven't yet heard what magic the engineer will work with my take-maps, but I should find out any day. And, in the meantime, I'm still savouring the memory of these sonatas as live performances. I have a long-abiding love-hate relationship with adrenaline -- but, listening through my 300 takes, meditating on the vicissitudes of excitement, technical 'perfection' and musical sterility, I've never missed the concert stage more.

Although Paul and I were too distracted to make a video in the studio, we did get some photos.

Setting up beforehand:

Action shot (look closely!):

Taking a break, touching up the tuning:

And, as we played our last note, my E string snapped:

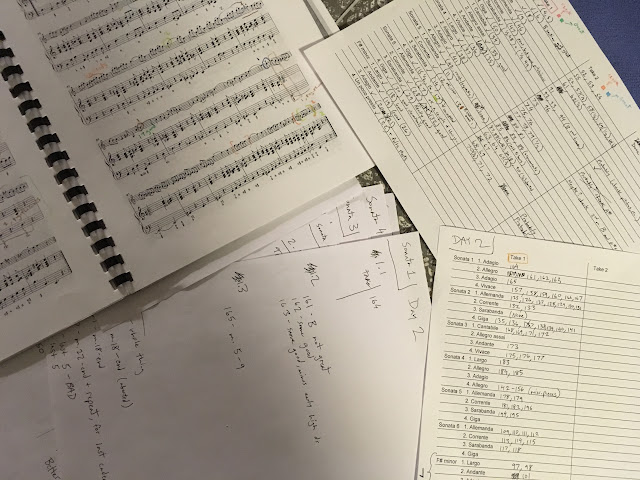

Birth of an 'interpretation':

Relics from a recital a week before the recording sessions. Having done these pieces in the studio, I almost don't remember what it was like to play them on stage.

Sonata II in D major:

To ease in, I'll start by posting a few photos and thoughts from my Telemann recording in mid June. My colleague Paul Cienniwa and I spent two days at WGBH in Boston recording seven early Telemann violin sonatas -- six from his brilliant Frankfurt collection, and one from the Dresden archives that will be a premiere recording. (Who knew there was still unrecorded Telemann out there?)

Although I've participated in other recording projects as part of orchestras and small ensembles, I've never done a solo project like this, so I've never had quite this level of artistic control. Needless to say, I'm still feeling my way through the process. There are so many trade-offs -- for instance, when the perfect takes feel a bit lifeless, but the exciting ones are all ragged. The number of possibilities, too, is numbingly vast. (I left the studio with 300+ takes of a mere 28 movements, and spent about two weeks weeding through them.) I surely knew, intellectually, at least, how artificial the recording process is, but none of my anti-recording philosophising prepared me for the experience of conjuring, take by take, a completely 'fake' interpretation: one in which I know I played every note, but which never, ever, sounded quite that way before, either in reality or in my imagination. And, with so much material, so much of it useable, I could have decided on any number of different final products. For some movements, I constructed four or five take-maps, all viable, and each with its own strengths. At best, it destabilizes the whole notion of the recording as document of an interpretation, and replaces it with that of recording as unconscious inventor of an interpretation.

There's an interesting contrast here with what various philosophers, most ably Taruskin in Text and Act, have said about live performances, recordings, and interpretations. Taruskin looks at a composer-performer like Stravinsky, whose many repeated recordings of his own works are so bewilderingly different, and so often diverge from performance instructions in the score, to argue that there is no such thing as a single 'Interpretation' of a piece of music, even (I say: especially?) by the work's composer. He begins from the 'evidence' of divergent recordings, and extrapolates to include live-performed interpretations on his list of nonexistent things. My experience suggests the opposite trajectory: for me as a performing musician/human, there is never a single interpretation of these works -- but in doing the recording and putting all the 'good' takes together and discarding the 'bad' I've had the rather disconcerting experience of watching an interpretation come to life, seemingly on its own, simply by piggy-backing on the good takes. On 17 June, there was no 'Interpretation'; now there is.

Ironically, and despite having watched the interpretation take shape, I still don't know quite what it will sound like, since I haven't yet heard what magic the engineer will work with my take-maps, but I should find out any day. And, in the meantime, I'm still savouring the memory of these sonatas as live performances. I have a long-abiding love-hate relationship with adrenaline -- but, listening through my 300 takes, meditating on the vicissitudes of excitement, technical 'perfection' and musical sterility, I've never missed the concert stage more.

***

Setting up beforehand:

Action shot (look closely!):

Taking a break, touching up the tuning:

And, as we played our last note, my E string snapped:

Birth of an 'interpretation':

Relics from a recital a week before the recording sessions. Having done these pieces in the studio, I almost don't remember what it was like to play them on stage.

Sonata II in D major:

Sonata V in A minor (don't miss the last movement!):